#10,365

After no reports for two days, the Saudi MOH is reporting their 8th MERS case in the past 8 days. This time from Al Kharj. Details, as always, are scant.

Raden Rahmad

Raden Rahmad

#10,365

After no reports for two days, the Saudi MOH is reporting their 8th MERS case in the past 8 days. This time from Al Kharj. Details, as always, are scant.

Raden Rahmad

Raden Rahmad

#10,364

When stories emerge about suspected links between an increased incidence of narcolepsy with taking the H1N1 Pandemrix vaccine, the elevated number of febrile reactions to CSL’s FluVax in Australia, or the possible impact of the (as-yet poorly understood) concept of Original Antigenic Sin on vaccines, it seems there is always a section of the anti-vaccine movement who will twist both the importance and meaning of these studies to fit their own agenda.

An indignity, I suspect, that yesterday’s PLoS Biology paper Imperfect Vaccination Can Enhance the Transmission of Highly Virulent Pathogens will also endure.

This immediate over-the-top `gotcha!’ response whenever researchers (or science writers) suggest that a vaccine might be less than perfect has a chilling effect, and I suspect serves as a barrier to development of better vaccines.

First, a quick look at this study – which deals with poultry vaccines for a specific herpesvirus (MDV), not human vaccines – followed by some discussion of how all this may relate to the recent proliferation of HPAI viruses around the world. The whole article is worth reading, so follow the link to read:

Research Article

Imperfect Vaccination Can Enhance the Transmission of Highly Virulent Pathogens

Andrew F. Read , Susan J. Baigent, Claire Powers, Lydia B. Kgosana, Luke Blackwell, Lorraine P. Smith, David A. Kennedy, Stephen W. Walkden-Brown, Venugopal K. Nair

Published: July 27, 2015

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002198

Abstract

Could some vaccines drive the evolution of more virulent pathogens? Conventional wisdom is that natural selection will remove highly lethal pathogens if host death greatly reduces transmission. Vaccines that keep hosts alive but still allow transmission could thus allow very virulent strains to circulate in a population.

Here we show experimentally that immunization of chickens against Marek's disease virus enhances the fitness of more virulent strains, making it possible for hyperpathogenic strains to transmit. Immunity elicited by direct vaccination or by maternal vaccination prolongs host survival but does not prevent infection, viral replication or transmission, thus extending the infectious periods of strains otherwise too lethal to persist.

Our data show that anti-disease vaccines that do not prevent transmission can create conditions that promote the emergence of pathogen strains that cause more severe disease in unvaccinated hosts.

Author Summary

There is a theoretical expectation that some types of vaccines could prompt the evolution of more virulent (“hotter”) pathogens. This idea follows from the notion that natural selection removes pathogen strains that are so “hot” that they kill their hosts and, therefore, themselves. Vaccines that let the hosts survive but do not prevent the spread of the pathogen relax this selection, allowing the evolution of hotter pathogens to occur.

This type of vaccine is often called a leaky vaccine. When vaccines prevent transmission, as is the case for nearly all vaccines used in humans, this type of evolution towards increased virulence is blocked. But when vaccines leak, allowing at least some pathogen transmission, they could create the ecological conditions that would allow hot strains to emerge and persist. This theory proved highly controversial when it was first proposed over a decade ago, but here we report experiments with Marek’s disease virus in poultry that show that modern commercial leaky vaccines can have precisely this effect: they allow the onward transmission of strains otherwise too lethal to persist.

Thus, the use of leaky vaccines can facilitate the evolution of pathogen strains that put unvaccinated hosts at greater risk of severe disease. The future challenge is to identify whether there are other types of vaccines used in animals and humans that might also generate these evolutionary risks.

This study suggests (at least with MDV and its imperfect vaccine) – to paraphrase Nietzsche – that which does not kill the virus, only makes it stronger.

Kai Kupferschmidt, writing for Science Magazine, has an excellent review of this article called Could some vaccines make diseases more deadly?, including reactions from other scientists. Rather than re-invent that wheel, I’ll simply refer my readers to that report, and move on to a related subject.

While above research suggests that imperfect vaccines have have led to the creation of a `hotter’ MVD strains - in the avian flu world we’ve recently seen a rapid rise in the number of novel flu subtypes - which many researchers also attribute to the use of poorly matched, or inconsistently applied vaccines.

Three years ago, we essentially had only one HPAI (Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza) virus of real concern; H5N1 – along with a handful of (mostly) low path (LPAI) H5, H7 and H9 viruses.

Since the spring of 2013 we’ve seen multiple new subtypes (H7N9, H10N8, H5N6, H6N1, H5N2, H5N3, H5N8, H5N9 (often with multiple clades)) emerge – mostly from China. A new clade of H5N1 (see Eurosurveillance: Emergence Of A Novel Cluster of H5N1 Clade 2.2.1.2) has appeared in Egypt, and that appears to be the driver for their unprecedented surge in human infections.

According to 2012’s Impact of vaccines and vaccination on global control of avian influenza by David Swayne, more than 113 billion poultry vaccine doses were used from 2002 to 2010. Two countries accounted for nearly 96% of all the vaccine used; 1) China (90.9%), 2) Egypt (4.6%).

Despite a decade’s heavy use of HPAI poultry vaccines, both Egypt and China continue to battle frequent outbreaks of HPAI in their poultry, and spillovers into the human population. The chart below is just for H5N1, and does not reflect the 640+ H7N9 cases in China, or the smattering of H5N6, H10N8, and H9N2 infections.

Over the past 8 months roughly 180 Egyptians have contracted H5N1 from contact with infected poultry, and we’ve seen reports of large numbers of poultry outbreaks – even among previously vaccinated poultry (see Egypt H5N1: Poultry Losses Climbing, Prices Up 25%).

Not surprisingly, in 2012’s Egypt: A Paltry Poultry Vaccine, we saw a study conducted by the Virology department at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital that looked at the effectiveness of six commercially available H5 poultry vaccines then deployed in Egypt, and found only one (based on a locally acquired H5N1 seed virus) actually appeared to offer protection.

The reality is, poultry vaccines don’t always prevent disease – sometimes they only mask the symptoms of infection, and that can not only allow viruses to spread stealthily, it can also put human health at risk.

The story in China has been much the same. Last November the EID Journal dispatch Subclinical Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus Infection among Vaccinated Chickens, China found evidence to suggest that `imperfect’ vaccines were driving the evolution of new clades, and and the creation of subtypes (bolding mine).

HPAI mass vaccination played a crucial role in HPAI control in China. However, this study demonstrated multiple disadvantages of HPAI mass vaccination, which had been suspected (13,14). For example, this study showed that H5N1 subtype HPAI virus has evolved into multiple H5N2 genotypes, which are all likely vaccine-escape variants, suggesting that this virus can easily evolve into vaccine-escape variants.

This observation suggests that HPAI mass vaccination, which is highly effective in the beginning of an outbreak, may lose its effectiveness with time unless the vaccine strains are updated. Moreover, this study showed that vaccinated chicken flocks can be infected with vaccine-escape variants without signs of illness.

Another study, released in February - Recombinant H5N2 Avian Influenza Virus Strains In Vaccinated Chickens - stated in its cautionary discussion (bolding mine):

In this study, three H5N2 influenza virus strains isolated from chickens were identified as novel reassortants with a highly pathogenic viral genotype. Surprisingly, the affected birds had been vaccinated with killed influenza vaccines but still showed characteristic clinical symptoms of avian influenza and eventually died.

These results are in agreement with previous work indicating that AIVs can continue genetic evolution under vaccination pressure [20]. Moreover, this study highlights the importance and necessity of periodic reformulation of the vaccine strain according to the strains circulating in the field in countries where vaccines are applied to control avian influenza.

Vaccines – even less than perfect ones – are often attractive options to poultry producers and governments facing serious social and economic disruptions from avian flu outbreaks (see Diseases of Food Animals Threaten Global Food Security).

Quarantine and culling – which are the preferred control methods in most of the world – are particularly unattractive options in countries where there are high levels of food insecurity or a high reliance on poultry for income or personal wealth.

For more than a decade, however, the OIE has warned that vaccination of poultry cannot be considered a long-term solution to combating avian flu. And that “Any decision to use vaccination must include an exit strategy, i.e. conditions to be met to stop vaccination”. – OIE on H7N9 Poultry Vaccines.

Despite these warnings, and the diminishing effectiveness of their vaccines these heavily impacted countries appear no closer to looking for that recommended `exit’. The lesson here is that starting a vaccination program is infinitely easier than ending one.

With avian flu threatening to return this fall, many poultry producers in the United States are clamoring for the USDA to approve the use of an HPAI H5 vaccine, something that our government – and indeed most governments around the globe – have so far been reluctant to do.

The most immediate concern is that deploying a bird flu vaccine could seriously impact our poultry exports, as many countries will refuse to accept vaccinated poultry products. This could literally cost the industry billions.

While their are probably situations where limited (and hopefully temporary) use of a poultry vaccine may make sense - the track records of AI poultry vaccine use in China and Egypt show that poultry vaccines haven’t proved to be any sort of panacea for their poultry industry.

Granted, their application may have reduced some short-term economic pain. But after ten years of vaccine use, their bird flu problems only appear to be getting worse.

Meaning there are far more issues for the USDA to weigh this fall when it comes to authorizing a bird flu vaccine for the United States, than just how it might affect exports.

Raden Rahmad

Raden RahmadCredit ECDC – Global Export Of MERS – Jul 21st, 2015

UPDATED: 7/28/15 0930 HRS

Crof has a report indicating that both UK: Manchester patients test negative for MERS

# 10,363

Although they have not been confirmed positive yet, earlier today the UK’s NHS announced that two suspected MERS cases had shown up at the Manchester Royal Infirmary A&E, and for the past several hours that department has been closed to the public.

While test results are still pending, and both cases have been placed in isolation, the hospital now reports their A&E is now open.

This afternoon, we confirmed that we are currently investigating two patients for suspected Middle Eastern Respiratory Virus Syndrome - Coronavirus Infection (MERS-COV).

Both patients were isolated for on-going management of their condition while tests took place. One patient has now been relocated to North Manchester General. Results of the tests are still pending.

Manchester Royal Infirmary A&E is open to the public. We would like to reassure our patients and the general public that there is no significant risk to public health.

Whether either one of these two cases end up being confirmed as having the MERS coronavirus (and we should know in the next 12 to 24 hours – updated UK: Manchester patients test negative for MERS), this is a not-so-subtle reminder that someone with an exotic infectious disease - like MERS, avian flu, Ebola, or Lassa fever – can show up at the door to the emergency department of any hospital in the world.

While infection control disasters – like what we saw with MERS in South Korea – are always possible, the good news is we’ve seen most of these types of imported cases quickly contained.

That said, a few weeks ago in Eurosurveillance: Estimating The Odds Of Secondary/Tertiary Cases From An Imported MERS Case, we looked a some modeling that put the odds of seeing at least one secondary case derived from an imported MERS case at 22.7% , while the odds of seeing at least one tertiary case is 10.5%.

Based on their models, however, they calculated the odds of seeing at least 8 cases as the result of a single importation at a non-trivial 10.9%.

Making their interdiction even more difficult, the long incubation period (up to 14 days) and common early symptoms makes detection of infected passengers at the airport a long-shot (see Why Airport Screening Can’t Stop MERS, Ebola or Avian Flu).

In June the CDC released updated guidelines for healthcare providers (see CDC Releases HAN #380 On MERS) and held a COCA Call (see Updated Information & Guidelines For Evaluation Of MERS) to help bring clinicians up to speed on this potential threat. If you haven’t had a chance to listen, you can hear the audio and read the transcript at the link below:

Updated Information and Guidelines for Evaluation for MERS

Overview

On May 20, 2015, the Republic of Korea (Korea) reported to the World Health Organization an initial case of laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV infection, the first case in what is now the largest single outbreak of MERS-CoV outside of the Arabian Peninsula. During today’s call, clinicians will be provided information about the global situation and the current status of the MERS-CoV outbreak in the Republic of Korea, updated guidance to healthcare providers and state and local health departments regarding who should be evaluated and tested for MERS-CoV infection, and further guidance on “Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Hospitalized Patients with Possible MERS-CoV.”

Call Materials

- Audio:Listen Now

- Transcript:Read Now

Around the same time APHA (American Public Health Association) weighed in with a summary report (see below) on the CDC's MERS guidelines, along with a handy poster for the public on how they should deal with the MERS threat (much of which would be applicable for almost any infectious disease).

Just over a month ago, in TFAH Issue Brief: Preparing The United States For MERS-CoV & Other Emerging Infections, we looked at the commitments that governments, healthcare facilities, and public health departments around the world need to take in order to prepare for the arrival of MERS and other Emerging infections.

Another complicating factor, in recent weeks we’ve looked at a pair of studies that call into question both the quality of some PPEs (Personal Protective Equipment) used by Health Care Workers, and their techniques in donning and doffing them safely.

Last week’s NIOSH Science Blog: Not All Isolation Gowns Tested Met Standards, found roughly 1/3rd of isolation gowns wanting in some aspect, while a recent APIC study suggests that Most HCWs Are Removing PPEs Improperly.

Whether MERS, Ebola, or Avian flu ever develop into a full fledged global health threat is unknown. At some point, the odds are something will. But for now, we can be grateful that most of the suspected cases will be false alarms and will provide opportunities for HCWs to improve their infection control skills.

The best case scenario is we learn to play this global game of Whac-a-MERS (or Ebola, or H5N1, etc.) exceedingly well, and whenever one of these imported cases pops up, we contain it before it can spread.

But for that to work, every healthcare facility – large and small - needs to plan, train and equip themselves for the possibility that the next patient that comes through the ER entrance could be carrying something considerably more exotic than the flu.

Raden Rahmad

Raden Rahmad

Lower Saxony – Near Dutch Border – Credit Wikipedia

#10,362

Roughly three weeks after the UK reported an outbreak of HPAI H7N7 (see Defra: Lancashire Avian Flu Confirmed As HPAI H7N7), today we learn from the Lower Saxony Ministry of Agriculture of a similar outbreak involving 10,000 layer hens at a farm in Emsland.

While it has been HPAI H5 avian flu viruses that have captured the bulk of our attention over the past dozen years, in the `also ran’ category are a growing variety of both low and high path H7 viruses. Until the emergence of H7N9 in China in 2013 – and the resultant infections (and in some cases, deaths) of hundreds of people – H7 viruses as a group were considered a low threat to public health.

China’s emerging H7N9 virus is a reminder that one should not get too comfortable with the track record of any flu subtype, as past performance is no guarantee of future results.

For now, however, H7 viruses other than China’s H7N9 are considered to pose a low threat to human health, as nearly all reported infections have been mild – often producing little more than conjunctivitis (see ECDC Update & Assessment: Human Infection By Avian H7N7 In Italy).

H7’s , however, are considered a serious threat to the poultry industry, and have caused hundred of millions of dollars in losses over the years.

There are two broad categories of avian influenza; LPAI (Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza) and HPAI (Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza).

This statement from the http://www.niedersachsen.de website.

(machine translation)

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H7N7 in the Emsland district

Investigations in LAVES and FLI confirm the self-check-result

HANNOVER. In Emsland the highly pathogenic form of bird flu has been found in a herd of hens. Affected is a company with about 10,000 laying hens in floor management that have been humanely killed. Suspected bird flu had resulted from self-monitoring results, which have now been confirmed by official samples of LAVES. In addition, it is clear, according to studies in the national reference laboratory of the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute (FLI) on the island Riems, that it was the highly pathogenic form of avian influenza (HPAI) is with subtype H7N7.

Experience has shown that it appears to come from animals to humans only in close contact with diseased or dead birds and their products or excretions of transmitting viruses. One should avoid direct contact with infected animals so sure. All necessary measures to combat the disease are set by European and federal regulations by the Emsland district Based on the official result. At the outbreak of highly pathogenic influenza form they relate, inter alia, the establishment of a Sperrbezirkes with three kilometers radius around the outbreak and operation of a monitoring area with a radius of ten kilometers. Poultry shall not be moved from these areas out in these areas or screwing in. Within a radius of one kilometer around the affected operating stocks are also animal welfare compliant killed - in this case about 60 animals from two animal facilities.

In addition, epidemiological investigation be undertaken to determine the cause and other contact holdings. Shall take effect 30 days after cleansing and disinfection operation no new case, these measures can be lifted. In Lower Saxony, outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza type H5N8 December 2014 were observed in the district of Cloppenburg and in the Emsland district recently. In March and in June this year, there was in the district of Cuxhaven and in the Emsland district outbreaks of low pathogenic form of avian influenza type H7N7.

For years, it comes again and again to the world outbreaks. With nearly 50 million so far this year were affected animals in particular the United States affected by severe HPAI cases. HPAI caused by avian influenza viruses, of which there are a variety of subtypes. An entry in domestic poultry is usually indirectly via virus-contaminated people and vehicles or excretions. In stock transfer is usually directly from animal to animal.

In Germany, regular monitoring tests for avian influenza in poultry flocks and in wild birds will be held. These have so far found no evidence of an influenza occurrence in Lower Saxony. Moreover, there is in poultry flocks special control inspections. All poultry farmers are urged to check their bio-security measures and apply them consistently. More information is available at www.tierseucheninfo.niedersachsen.de be viewed.

Raden Rahmad

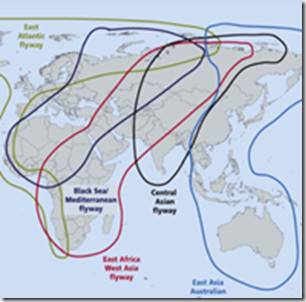

Raden RahmadMajor Global Migratory Flyways – Credit FAO

#10,361

A decade ago, when H5N1 was making its first forays into Europe and the Middle East, concerns ran high it might hitch a ride on migratory birds and make its way to the Americas. As the map above illustrates, there are two major `shared’ migratory flyways which could plausibly provide a bridge for avian flu from either Europe or Asia.

While primarily north-south migratory routes, these flyways all overlap, and therefore allow for lateral (east-west) movement of birds as well. A good example this comes from our own Arctic Refuge, where more than 200 bird species spend their summers, and then head south via all four North American Flyways each fall.

Credit FWS.GOV

In 2008, a USGS study found Genetic Evidence Of The Movement Of Avian Influenza Viruses From Asia To North America, where we saw evidence that suggested migratory birds play a larger role in intercontinental spread of avian influenza viruses than previously thought.

A couple of years later, in Where The Wild Duck Goes, we looked at a USGS program that used Satellite Tracking To Reveal How Wild Birds May Spread Avian Flu.

For reasons that remain obscure, in 2007 the aggressive global expansion of H5N1 halted, and over the next few years we saw a retreat of the virus from across much of Europe, with most of the activity centered around Asia, India, Indonesia, and Egypt.

While concerns over H5N1 winging its way to the Americas didn’t go away, they were at least dampened.

Although research has continued to implicate wild and migratory birds as vectors of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) viruses, the idea has not been without its critics.

For years we’ve heard from some experts that `Sick birds don’t fly’ , even though it has been well established that some bird species can carry HPAI viruses asymptomatically (see Webster On China's `Silent' Bird Flu Infections). A few notable dissenting voices include:

1. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreaks are most frequently associated with domestic poultry production systems and value chains.

2. H5N8 HPAI virus has recently emerged in domestic poultry in the Republic of Korea and has caused mortality of domestic poultry and wild birds.

3. As well as impact on the poultry industry, there is the potential for significant mortality of wild birds most notably in large flocks of Baikal teal.

4. There is currently no evidence that wild birds are the source of this virus and they should be considered victims not vectors.

We’ve explored this often bitter debate between the poultry industry and conservationists a number of times (see Bird Flu Spread: The Flyway Or The Highway?) and while poultry industry practices and poor biosecurity are no doubt major contributing factors for the spread of avian flu, it is hard to dismiss wild birds as being at least partially responsible, particularly for long distance jumps of the virus.

For a full decade following the second emergence of H5N1 in Vietnam (2003), the bird flu scene remained fairly stable. There was HPAI H5N1, and a handful of lesser LPAI (low path) H5 and H7 viruses of concern (plus LPAI H9N2), but only one HPAI threat.

Things began to get messy in 2013, when a new LPAI H7N9 virus appeared in China. While it didn’t make birds sick, it was highly pathogenic in humans, and it has sparked three mini-epidemics since its arrival. Since it is asymptomatic in birds, it spreads stealthily in poultry flocks and live markets, making it very difficult to detect and control.

A few months later an HPAI H10N8 appeared in China, causing several deaths, followed by HPAI H5N8 which showed up in South Korean migratory birds – and commercial poultry – in January of 2014. Not to be outdone, a new H5N6 virus appeared in both China and Vietnam in the spring of last year, and much like H5N1, it can infect (and kill) humans.

HPAI H5N8 quickly spread across China and into Russia, but a big surprise came last November when a farm in Germany reported the virus (see Germany Reports H5N8 Outbreak in Turkeys), followed 10 days later by reports from the Netherlands (see Netherlands: `Severe’ HPAI Outbreak In Poultry), and again from Japan (see Japan: H5N8 In Migratory Bird Droppings).

H5N8 Branching Out To Europe & Japan

Suddenly H5N8 was on the move, in a manner which we hadn’t seen since the great H5N1 diaspora of 2006 – when that virus sprang out of southeast Asia and moved into Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

An even bigger surprise came when HPAI H5 virus literally jumped continents and turned up – first in Canada’s Pacific Northwest (see Fraser Valley B.C. Culling Poultry After Detecting H5 Avian Flu) in early December – and then began spreading across the western United States (see EID Journal: Novel Eurasian HPAI A H5 Viruses in Wild Birds – Washington, USA).

.

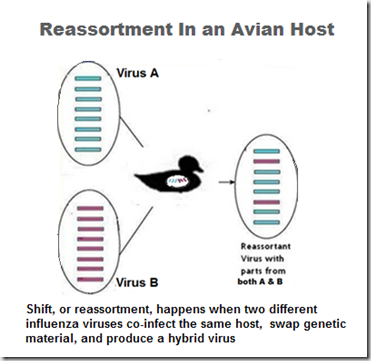

As H5N8 arrived in Taiwan, Canada, and the United States, it has reassorted with local LPAI viruses and produced unique reassortant viruses (H5N2 and H5N1 in North America, H5N2, H5N3 in Taiwan).

How viruses shuffle their genes (reassort)

Not only has H5N8 proved to be an able hitchhiker aboard migratory birds, it appears to reassort easily with other LPAI viruses, and has churned out a remarkable number of viable offspring in a short period of time.

Of these, H5N2 has spread the fastest, and caused the most damage to the poultry industry. But the possibility of seeing additional reassortments emerge in the years to come is real, and their behavior – and their pathogenicity in birds and humans – is quite frankly, impossible to predict.

The $64 question is what comes next.

And quite frankly, no one knows. In 2007, just when it looked as if H5N1 was on the verge of becoming a global threat, it unexpectedly began to wane. The same thing could happen again, although this time the HPAI bench is deeper, as it includes H5N1, H5N2, H5N8, H5N6, and H7N9 (among others).

The expectation is that H5N8/H5N2 will return with the fall arrival of migratory birds, and if farm biosecurity measures aren’t effective - we could see a repeat of this past spring – except more states and more farms are likely to be impacted.

If that happens, it could cost the poultry industry billions, which is why on Tuesday, Secretary of Agriculture Vilsack will be meeting with state and local officials, and representatives of the poultry industry, in Des Moines, Iowa to discuss preparing for this exact possibility.

There are other scenarios, of course.

The same avian flu scenarios facing North America this fall and winter pose similar threats to much of Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Only the flyways that will serve as potential bird flu conduits differ.

If there are any doubts remaining over the role that migratory birds are playing in the spread of avian flu viruses, with the scrutiny they will get this fall and winter (see APHIS/USDA Announce Updated Fall Surveillance Programs For Avian Flu), there’s a pretty good chance they will be resolved over next 6 months to a year.

For more on the spread of avian viruses across long distances by migratory birds, you may wish to revisit:

Erasmus Study On Role Of Migratory Birds In Spread Of Avian Flu

PNAS: H5N1 Propagation Via Migratory Birds

EID Journal: A Proposed Strategy For Wild Bird Avian Influenza Surveillance

Raden Rahmad

Raden Rahmad

#10,360

After several fairly quiet weeks, MERS reports are starting to pick up again in Saudi Arabia, with 7 cases reported over the past 5 days – 6 of which have centered around Riyadh.

Although the source of exposure was not provided for the first 5 cases, the latest two cases are listed as having `Contact with suspected or confirmed cases in community or hospitals’.

Whether this means they are the result of a family cluster, or another nosocomial outbreak, isn’t clear. In any event, the details on the latest case read:

src="https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh4zgoKkY5esDyGDfXmhp5tz0W8H2jEgsRJx2wm9317hpr6CTdO8i4DPQj5mF-OAprw6GVcNt84Pt9Yp5U6XEz5h_pAP7azclFEO7kSUzDjr31IvLdzT01usqHnjVk1bBWsqpHQX6G4AIU/s1600/Photo0783.jpg" />

src="https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh4zgoKkY5esDyGDfXmhp5tz0W8H2jEgsRJx2wm9317hpr6CTdO8i4DPQj5mF-OAprw6GVcNt84Pt9Yp5U6XEz5h_pAP7azclFEO7kSUzDjr31IvLdzT01usqHnjVk1bBWsqpHQX6G4AIU/s1600/Photo0783.jpg" />